The concept of medical labeling standards underscores that the safe operation of a medical device must never hinge on guesswork or trial and error.

These standards ensure that informative, accurate labeling is not just an option but a necessity, with every label that accompanies the device needing to comply with the pertinent medical device labeling requirements and regulations.

When features or hazards are inadequately labeled, the door is opened to misuse, which can cause harm to the user and erode trust in the device’s reliability. Proper labeling is instrumental in preventing errors, guaranteeing that users safely obtain the intended benefits of the device.

Labeling transcends being a mere formality in the production process for medical device manufacturers; it is indispensable. Without the necessary labels, devices cannot be released into the market.

Regulations govern all aspects of labeling, from the design of the labels to the methods used to affix them to a device, necessitating that manufacturers accord labeling the same level of importance as every other facet of product quality assurance.

This discussion aims to illuminate what constitutes a medical device label, delineate where such labeling is imperative, and delve into the critical aspects of medical device labeling regulations both in the United States and the European Union.

Following this exploration, we will offer general guidelines designed to assist manufacturers in crafting labels that not only benefit their customers but also comply with regulatory requirements, ensuring that their devices are used safely and effectively.

What exactly qualifies as a medical device in legal terms?

Legally, the FDA’s definition encompasses any item that is used to diagnose, cure treat, or prevent diseases or health conditions, or that significantly alters the structure or function of the body. This broad category includes various forms of instruments, apparatus, machines, implants, or in vitro reagents, as well as any parts, components, or accessories related to these devices.

Notably, substances that are metabolized by the body, such as drugs, do not fall under the “device” category. Interestingly, software also enters the realm of medical devices if it directly contributes to any of the aforementioned functions, though software merely used for storing data or administrative purposes is excluded.

In a similar vein, the European Union’s Medical Device Regulation identifies medical devices as non-pharmacological products that are designed to diagnose, cure, and/or prevent medical conditions and diseases. These devices may also be used to investigate anatomical, physiological, or pathological processes for the purpose of replacement and/or modification, or to collect and preserve samples from human patients for medical analysis.

The FDA also regulates the labeling and classification of over the counter devices. These devices must adhere to specific labeling requirements to ensure compliance with health regulations, including clear warnings and labeling practices to inform consumers.

The question of which party within a device’s supply chain is responsible for its labeling may not always present a clear answer. Typically, the responsibility falls to the device manufacturer, yet there are instances where other parties involved might also bear labeling duties. This list can be extended to include:

- Re-processors of previously used devices,

- Re-packagers of devices,

- Entities that re-label devices,

- Kit assemblers compile various device components,

- Specification developers provide detailed device descriptions,

- And even manufacturers who are uncertain of their specific labeling obligations.

For manufacturers grappling with uncertainties regarding their labeling responsibilities, it is advisable to consult the guidelines issued by their governing regulatory body. This step ensures compliance and fosters a clearer understanding of their roles in safeguarding consumer safety through proper device labeling.

What must manufacturers know about medical device labeling regulations?

In both the United States and the European Union, the stipulations for labeling medical devices are meticulously detailed and comprehensive, often tailored to the device’s specific category.

It’s imperative for manufacturers to consult the exact wording of the relevant statutes and regulations directly, ensuring their practices align precisely with legal requirements and maintain compliance.

This diligence is crucial not only for adherence to legal standards but also for the safety and informed usage of medical devices by healthcare professionals and patients alike.

The US FDA mandate for medical device labels

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines a label as any “display of written, printed, or graphic matter upon the immediate container of any article,” necessitating clear visibility even when the “immediate container” is further enclosed.

The term “label” further encompasses any printed material on a product container or wrapper, or any item accompanying the product at the point of sale. Through this broad definition, US courts have determined that advertising, posters, brochures, instruction manuals, inserts, and any analogous materials are also categorized as labels for regulatory oversight.

Specific labeling requisites are enumerated in CFR Title 21, Part 801, which dictates that FDA-compliant labels must feature:

- The manufacturer’s name and business address,

- The intended application of the device,

- Comprehensive instructions that enable a layperson to utilize the device safely without professional assistance.

Labels must eschew any false or misleading assertions and be conspicuously placed at a suitable site on the packaging.

Furthermore, the FDA obligates manufacturers to incorporate Unique Device Identification (UDI) labels to facilitate the precise tracking of devices. These UDIs must be readable by both humans and machines, ensuring that the tracking elements meet rigorous standards for clarity and accessibility.

The stipulations for labeling under the EU MDR

The European Union’s Medical Device Regulation (MDR) encompasses its labeling regulations within Annex I, Chapter III. These regulations broadly correspond with the FDA’s, inclusive of the mandate for Unique Device Identification (UDI) on labels.

Beyond affixing labels directly to the medical device or its packaging, where relevant, EU manufacturers are also compelled to provide current labeling information via their corporate website. This requirement ensures transparency and accessibility of information, allowing end-users and regulatory bodies to easily access and review labeling details pertinent to medical devices, including the unique device identifier for traceability and compliance.

Why must medical device labeling be given paramount importance?

Clear and precise labeling on medical devices holds critical significance, especially since many such devices are intended for use by patients at home, without the supervision of healthcare professionals.

Maintaining a comprehensive device history record is crucial for compliance and safety, as it includes inspection results, updated labeling information, and standard operating procedures, thus facilitating adherence to FDA requirements.

For the assurance of safety and effectiveness, not only patients but also medical professionals and seasoned users rely heavily on lucid instructions, guidance, and cautionary details.

In instances of misuse or incorrect handling, the repercussions for the user can range from the device’s malfunction to severe injury or even fatality. Even minor missteps can have adverse effects on patient health outcomes.

For every party involved in the device’s lifecycle—from design to delivery—the well-being of the end-user should be the utmost priority.

Sound labeling practices serve as a vital tool to curtail adverse incidents and to uphold confidence in medical devices. Moreover, these practices are not just about safeguarding user health; they are also about adherence to regulatory standards.

Effective labeling can prevent the setbacks of non-compliance, such as costly hold-ups, recalls, or legal issues, thereby ensuring uninterrupted delivery of medical devices to the market.

The key principles for crafting medical device labels

Constructing an exemplary medical device label is not a pursuit of a universal template but a nuanced process. The crucial elements vary significantly based on a myriad of factors, with the onus on manufacturers to ensure the inclusion of all vital components.

The goal of a label is not just to fulfill regulatory mandates but to ensure that it imparts all the information necessary for the patient to gain a positive outcome from the device’s use.

To achieve such an objective, here is an expanded outline of best practices for the development of effective and compliant labels:

- Initiate label design considerations at the earliest stages of product development, to integrate labeling seamlessly with the design and function of the device.

- Adhering to quality system regulation is crucial in the labeling process to ensure compliance with FDA’s requirements outlined in 21 CFR Part 820.

- Diligently consult the specific guidelines set forth by your regulatory body to ascertain the full scope of information mandated for inclusion, particularly within the directions for use.

- Employ standardized symbols that comply with international regulations to ensure universal comprehension and use.

- Opt for robust label materials capable of withstanding repeated cleaning and sterilization processes while maintaining legibility.

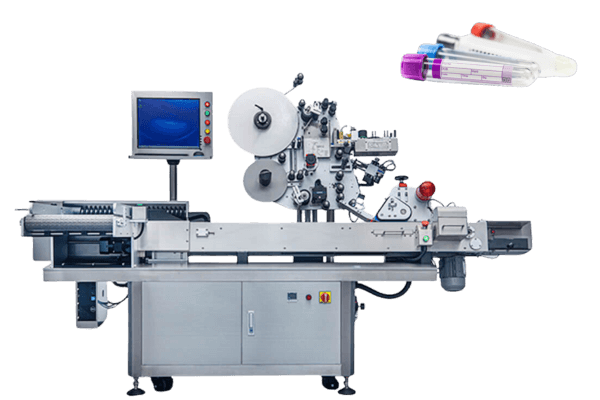

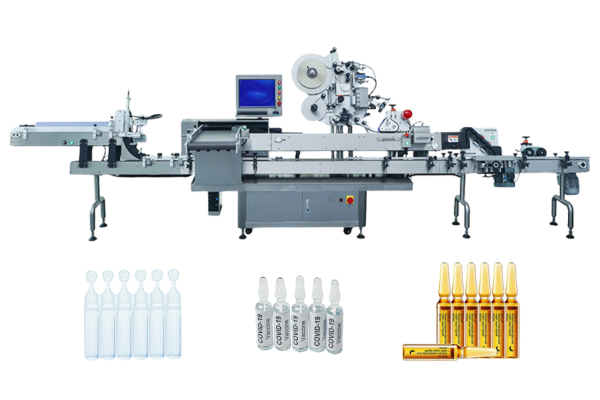

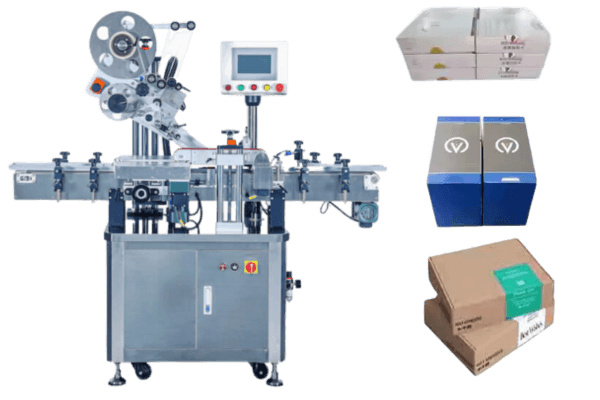

- Streamline label production through automation to enhance consistency and reduce the likelihood of human error.

- Create adaptable label templates that are easily updated with the necessary information to expedite the labeling process for various products.

- Collaborate closely with supply chain partners to synchronize compliance efforts and avoid redundant labeling tasks.

- Conduct thorough usability tests to confirm that the intended message of your labels is accurately interpreted and understood by users.

- Incorporate comprehensive warnings that detail all known risks and clearly state the implications of off-label use.

- Before solidifying your labeling approach, conduct a thorough review of the legal framework to determine any additional, specialized labeling requisites relevant to your specific medical devices. This step ensures that your labels are not only informative but also legally compliant, aligning with the most recent regulations and standards.

QMS and medical device labeling

A Quality Management System (QMS) that is meticulously tailored to the unique demands of medical device manufacturers serves as an essential backbone, ensuring compliance with regulatory requirements and supporting the production of labels that reflect the high quality of the devices they accompany.

An effective QMS solution will bolster labeling protocols by maintaining current manufacturing data, meticulously tracking revisions to documents, and verifying that every aspect of the labeling process is in strict conformance with all pertinent regulations.

Moreover, the deployment of a QMS is instrumental in creating a standardized approach to labeling, where consistency in label quality becomes as critical as the device’s quality. The system aids in identifying potential non-conformities before they become issues, enhancing overall operational efficiency.

By incorporating a robust QMS, manufacturers can rest assured that their labels are accurate, up-to-date, and fully aligned with the standards set by the industry, thereby fortifying the trust and safety of healthcare providers and patients alike.

Possible future directions for medical device labeling

As technology advances and the demands of the healthcare industry evolve, the future of medical device labeling is set to emphasize more on smart technologies, personalization, and environmental sustainability. Here are some anticipated trends:

- Integration of smart label technologies: Future medical device labels may incorporate advanced technologies such as NFC (Near Field Communication), RFID (Radio Frequency Identification), and sensors. These technologies could enable real-time tracking of device usage and location, enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of device management.

- Increased personalization and customization: With advancements in printing technologies, such as 3D printing, medical device labels could achieve higher levels of personalization and customization. Healthcare providers could tailor label content to meet specific clinical needs, better serving both patients and medical professionals.

- Use of eco-friendly materials: In response to growing environmental concerns, future labels are likely to utilize recyclable or biodegradable materials, reducing environmental impact and aligning with global sustainability efforts.

- Comprehensive regulatory compliance and safety information: As international regulations become more stringent, medical device labels will need to include more detailed safety instructions and compliance statements. This will help healthcare providers better understand and utilize devices while ensuring patient safety.

- Enhanced patient interaction: Labels might include interactive elements such as QR codes linking to instructional videos, user manuals, and other patient education resources. This interaction can encourage patients to take an active role in their treatment, improving adherence and outcomes.

Conclusion

In short, compliance with medical labeling standards is essential to safeguard patient safety and maintain trust in medical devices, and labeling machines play a central role in this.

We are a company that manufactures versatile pharmaceutical labeling machines that are designed to meet these standards for a wide range of medical device applications, including vials, syringes, and ampoules. For manufacturers looking for reliability and compliance in the labeling process, we are your reliable partner!

References and citations

1.Edward M. Basile、Ellen Armentrout,Medical Device Labeling and Advertising: An Overview,Food and Drug Law Journal,Vol. 54, No. 4 (1999), pp. 519-533 (15 pages)